There is no definitive proof of exactly how or when the Rolling family came to King Township. After extensive research, however, it has been concluded that this is likely what happened:

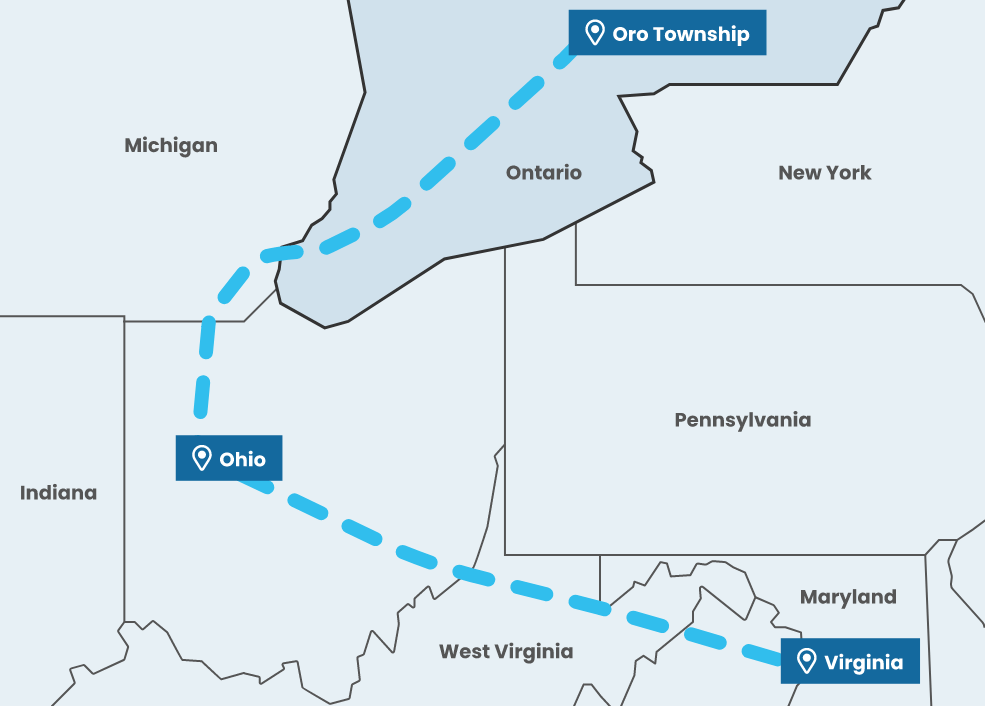

Benjamin Rolling Sr. was born in 1797 in Alexandria, Virginia. He was married to Almira who was born in 1801 in the United States. It is not known whether they were slaves or free Blacks, or why they left Virginia. They did appear in Ohio in 1822, when they their first daughter Charlotte Rolling was born. It is also not known if Almira and Benjamin were legally married. There were no legal marriages between slaves, and free Blacks had to find an anti-slavery clergyman to perform the ceremony for it to be considered legal. Many times, Blacks just held solemn ceremonies with their family and friends in attendance.

If the Rollings were slaves, Ohio was a passageway to Upper Canada on the Underground Railroad. It is estimated that by 1815, more than 1,000 slaves had travelled to Upper Canada via the Ohio River. If the Rollings were free Blacks, Ohio had fewer restrictions than Virginia. In Virginia, the free Blacks needed to be registered, could only work certain jobs and live certain places. It seemed that free blacks were caught in a 'no man's land' between slavery and freedom. Compared to the Whites, they were barred from schools, could not vote, were physically threatened, and could not change their economic position.

Many White people believed that free Blacks were considered dangerous. Free Blacks were an anomaly. If they achieved success in business or life, this contradicted the mythology of White supremacy that many Whites thought as the norm.

Even though Ohio was a better place for Blacks to live than Virginia, the conditions were still not ideal. Many people in that state did not disapprove of slavery even though Ohio was a "free state". Many settlers in the lower part of the state were originally from the Carolinas and Virginia where slavery did exist. Free Blacks and hired-out slaves lived wherever they could. They lived in shacks in alleyways, in makeshift houses on the edge of city limits, in basements, and outbuildings.

Many Blacks were surprised by the treatment they received when they moved to a free state like Ohio. They thought they would be treated as equals and have every opportunity. Instead, they found many doors closed due to the colour of their skin.

Many states, including Ohio, passed Black Laws, also called the "Black Code", which regulated the movements and liberties of free Blacks. In many places, the Code was meant to be a deterrence for Blacks to settle in that state and to limit the activities of the Blacks already living there with the aim to get them to leave. Ohio passed their Black Code in 1804, but it was not strictly enforced. The law was called An Act to Black and Mullatto Persons. It stated that Blacks could not live or work in Ohio without a Certificate of Freedom issued by the federal court. This document had to be carried with them at all times. In 1807, Blacks entering the state had to provide a $500 bond, signed by two White men, as a guarantee of their good behaviour. As the Black population grew, the more the Whites demanded the laws to be enforced.

By the 1820s, Ohio was a haven for Black immigrants from other states. In 1827, 10% of the urban population of Cincinnati was free Blacks. There was also an increase in White immigration from countries such as Ireland. This increase in immigrants resulted in competition between the Blacks and White for employment. One June 29, 1829 all Blacks were "put on notice" that the Black Code would be enforced and they had 60 days either to comply with the requirements or to leave. That meant that they had to post a $500 bond; they had to have their behaviour guaranteed by two White men of respectable station; observe curfew; and certain jobs from that point on would be reserved for Whites.

Then on July 27, 1829, the Cincinnati Gazette reported that if a resident employed a Negro or Mulatto person who caused an offence, they had to pay a fine of up to $100 and be liable for maintenance and support of that employee if they could not support themselves.

On August 22, 1829, three days of race riots broke out in Cincinnati. More than 300 Whites attacked the Blacks who lived in the city, who they felt were competing with them for jobs. The Blacks responded with gunfire.

With the implementation of the Black Code and riots in Ohio, in 1829 a group of largely free Black lead by James C. Brown, sent representatives to Lieutenant-Governor Sir John Colborne, seeking asylum in Canada. The government, directed by Colonel Edward George O'Brien, helped these Blacks to relocate to Oro Township, which is north of Barrie, Ontario. It is estimated that 460 Blacks immigrated to Canada during this time.

It is believed that Benjamin and Almira lived in Ohio during this time and came to Canada with this group. Records were found of them settling in Oro. Leaving their home country would not have been easy, but they would have had a growing concern for their welfare and the future freedom of their children. It was known that Canada could be a land of opportunity and a place where the Black Code did not exist. John Beverley Robinson, the Chief Justice of Upper Canada, developed the Fugitive Offenders Act in 1833 which stated that "Negroes in the country to which the formerly belonged, here they are free." It also stated that "for the enjoyment of all civil rights consequent to a mere residence in the country and among them the right to personal freedom as acknowledged and protected by the Laws of England...[must] be extended to these Negroes as well as to others under His Majesty's Government in this Province."

Courtesy of Huronia Museum

In 1829, Sir James Kemp, administrator of Lower Canada stated that "the state of slavery is not recognized in the Law of Canada nor does the Law admit that any man can be the proprietor of another." Even though the United States protested to Canada and the British Government to force Canada to return slaves, they were denied. The British Government stated that it would "never depart from the principle recognized by the British courts that every man is free who reaches British ground."

The community of Oro was established in 1819 by the government of Upper Canada. Land grants were offered here to Black veterans of the War of 1812.

Of these veterans, only nine families had established themselves there by 1831. Therefore, from 1828 to 1831, the government granted land to other Blacks, many of whom were from Ohio. Peter Robinson, the Commissioner of Crown Lands, sold 100 acre lots for one shilling per acre.

To gain title of the land, the owner had to clear a portion of the road adjoining the land, build a house of a certain size and clear 10 acres. By 1831, it was estimated that there were approximately 97 Blacks in Oro Township. That year, Peter Robinson did an inspection of these lands, and if these tasks were not complete, the residents were evicted from their land.

The census indicated that there was a Benjamin Rolling who had registered for a property in Oro Township: east half of Lot 8, Concession 5. In 1831, it was reported that he had left the lot and moved on. It is not known exactly why the Rolling family left Oro, but it could have been because of the poor land conditions, harsh climate and the remote and inaccessible location.

Blacks who came to Upper Canada by the early 1830s were tolerated but welcomed, as Canadians felt sympathetic and viewed them as temporary residents. The Blacks became a cheap source of labour for many Canadians. Blacks came to Canada in search of a better life with higher wages, social acceptability, and where basic human rights and freedoms were upheld.

By 1835, Benjamin Rolling was living south of Aurora in King Township. To know more about where they lived in King Township and what they did, click here.